STUDY FINDS THAT CAVITIES SCULPTED BY STELLAR OUTFLOWS DID NOT EXPAND OVER TIME

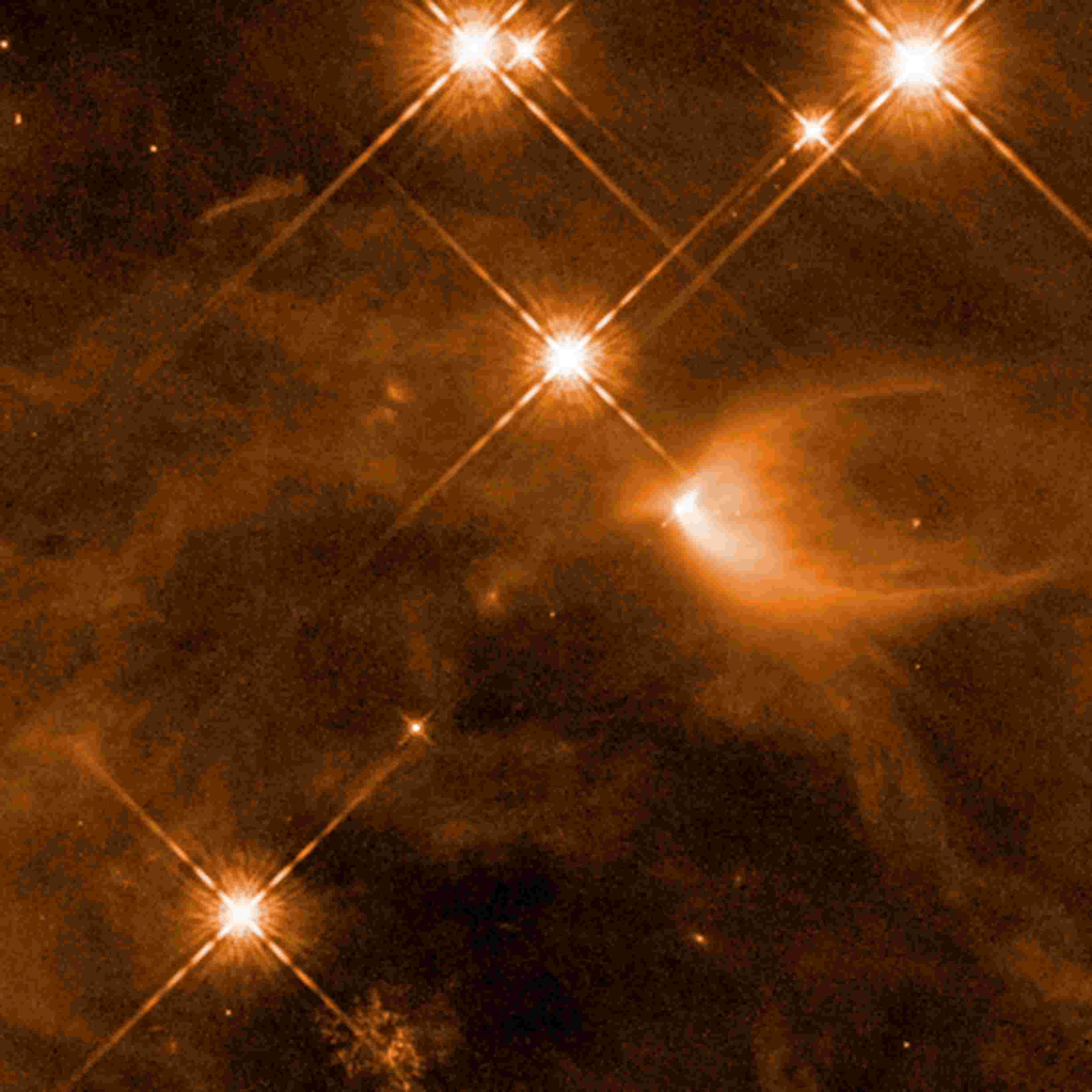

Stars aren't shy about announcing their births. As they are born from the collapse of giant clouds of hydrogen gas and begin to grow, they launch hurricane-like winds and spinning, lawn-sprinkler-style jets shooting off in opposite directions.

This action carves out huge cavities in the giant gas clouds. Astronomers thought these stellar temper tantrums would eventually clear out the surrounding gas cloud, halting the star's growth. But in a comprehensive analysis of 304 fledgling stars in the Orion Complex, the nearest major star-forming region to Earth, researchers discovered that gas-clearing by a star's outflow may not be as important in determining its final mass as conventional theories suggest. Their study was based on previously collected data from NASA's Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes and the European Space Agency's Herschel Space Telescope.

The study leaves astronomers still wondering why star formation is so inefficient. Only 30% of a hydrogen gas cloud's initial mass winds up as a newborn star.

Though our galaxy is an immense city of at least 200 billion stars, the details of how they formed remain largely cloaked in mystery.

Scientists know that stars form from the collapse of huge hydrogen clouds that are squeezed under gravity to the point where nuclear fusion ignites. But only about 30 percent of the cloud's initial mass winds up as a newborn star. Where does the rest of the hydrogen go during such a terribly inefficient process?

It has been assumed that a newly forming star blows off a lot of hot gas through light-saber-shaped outflowing jets and hurricane-like winds launched from the encircling disk by powerful magnetic fields. These fireworks should squelch further growth of the central star. But a new, comprehensive Hubble survey shows that this most common explanation doesn't seem to work, leaving astronomers puzzled.

Researchers used data previously collected from NASA's Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes and the European Space Agency's Herschel Space Telescope to analyze 304 developing stars, called protostars, in the Orion Complex, the nearest major star-forming region to Earth. (Spitzer and Herschel are no longer operational.)

In this largest-ever survey of nascent stars to date, researchers are finding that gas — clearing by a star's outflow may not be as important in determining its final mass as conventional theories suggest. The researchers' goal was to determine whether stellar outflows halt the infall of gas onto a star and stop it from growing.

Instead, they found that the cavities in the surrounding gas cloud sculpted by a forming star's outflow did not grow regularly as they matured, as theories propose.

"In one stellar formation model, if you start out with a small cavity, as the protostar rapidly becomes more evolved, its outflow creates an ever-larger cavity until the surrounding gas is eventually blown away, leaving an isolated star," explained lead researcher Nolan Habel of the University of Toledo in Ohio.

"Our observations indicate there is no progressive growth that we can find, so the cavities are not growing until they push out all of the mass in the cloud. So, there must be some other process going on that gets rid of the gas that doesn't end up in the star."

The team's results will appear in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

CREDITS:

NASA, ESA, and N. Habel and S. T. Megeath (University of Toledo)